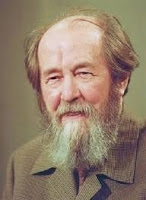

I well remember the very widespread custom, back in the South, of “twilighting.” Carried over from before the Revolution, it might have also been fortified by the meager, perilous years of the Civil War. Yet this practice had come about much earlier. Was it born of the months-long warmness of the Southern dusk? Many became accustomed never to rush lighting their lamps; yet, having completed their chores (or tended to the livestock) before nightfall, they were in no hurry to get to bed. Instead, they emerged outside to sit on dirt ledges, or benches, or just lounged inside with the windows wide open—no light to draw in bugs. One after another they would sit softly down, as if lost in thought. And long remained silent.Prose Poem by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

If someone did speak, it was quietly, delicately, unobtrusively. Somehow, in those exchanges, no one got fired up to argue, or to reproach spitefully, or to quarrel. Faces could barely be made out, then not at all; and, lo, one began to discern in them, and their voices, something unfamiliar, something one failed to observe through the prior course of years.

A feeling would take hold of everyone, of something impalpable and unseen that descended gently from the dimming after-sunset sky, dissolved in the air, streamed in through the windows: that profound seriousness of life, its unfragmented meaning, that goes ignored in the bustle of day. Our brush with the enigma that we let flit away.